Among the many non-human entities documented across Middle Eastern folklore, few inspire the same primal fear as the Ghul. Known as the flesh-eating djinn that stalks deserts, graveyards and forgotten places, the Ghul occupies a unique and deeply unsettling position within the wider paranormal landscape. Unlike many djinn, whose motivations and behaviours range from neutral to complex intelligence, the Ghul is almost universally described as predatory, deceptive and hostile to human life.

Origins of the Ghul in Arabian Paranormal Tradition

The word Ghul derives from the Arabic ghala, meaning “to seize”, “to overpower” or “to destroy”. This linguistic root is telling, as early references do not portray the Ghul as a passive spirit or wandering trickster, but as an active predator. In pre-Islamic Arabia, the Ghul was believed to inhabit desolate landscapes – particularly deserts, burial grounds and abandoned settlements – places already associated with spiritual thinness and heightened paranormal activity.

Bedouin accounts describe Ghuls as entities that hunt travellers, especially those who are alone or disoriented. These stories were not told as entertainment, but as warnings. The desert, both physically and spiritually, was seen as a liminal space where the boundary between the human world and the unseen weakened, allowing entities like the Ghul to manifest more freely.

With the rise of Islam, Ghuls were increasingly categorised within the broader classification of djinn, beings created from the elements and endowed with free will. However, unlike other djinn – who may coexist with humans or even avoid them entirely – the Ghul retained its reputation as an entity that actively seeks human flesh, particularly the dead.

The Ghul as a Flesh-Eating Entity

One of the most consistent traits of the Ghul across all sources is its association with corpse consumption. Graveyards, battlefields and execution sites were believed to attract Ghuls, not simply because of death, but because of the energetic residue left behind. From a paranormal perspective, these locations are charged environments, and Ghuls appear drawn to both physical remains and the lingering spiritual imprint of trauma.

Unlike Western undead traditions, the Ghul does not need to reanimate corpses. Instead, it consumes them. This distinction is critical. The Ghul is not the dead – it feeds on the dead. In some traditions, it is also said to attack the living, particularly those it has successfully lured or isolated.

This feeding behaviour suggests a parasitic relationship with human mortality itself, reinforcing the idea that the Ghul exists alongside humanity, feeding off its most vulnerable moments.

Shapeshifting and Deception

The Ghul is most dangerous not because of brute strength, but because of its ability to deceive. Numerous accounts describe Ghuls appearing as injured travellers, lost women, animals in distress or even familiar human figures. Once trust is established, the entity leads its target away from safety.

A recurring detail in traditional accounts is that no matter how convincingly the Ghul disguises itself, some element of its true form remains unchanged – often its feet, which may resemble hooves or animal legs. This detail appears across regions and centuries, suggesting a deeply ingrained understanding of the entities limitations.

From a paranormal investigation standpoint, this consistency mirrors what we see with many non-human entities: an ability to manipulate perception but not fully suppress their underlying nature.

How the Ghul Differs From Other Djinn

While the Ghul is often broadly labelled as a djinn, this classification can be misleading if treated too casually. Djinn are not a single entity type, but a vast and varied non-human category encompassing multiple species, temperaments and behavioural patterns. What separates the Ghu from most djinn is not origin, but function. Where many djinn coexist, observe or interact selectively with humanity, the Ghul operates almost exclusively as a predator.

Understanding these distinctions is critical when analysing an encounter, as misclassification can lead to incorrect assumptions about intent, risk and response.

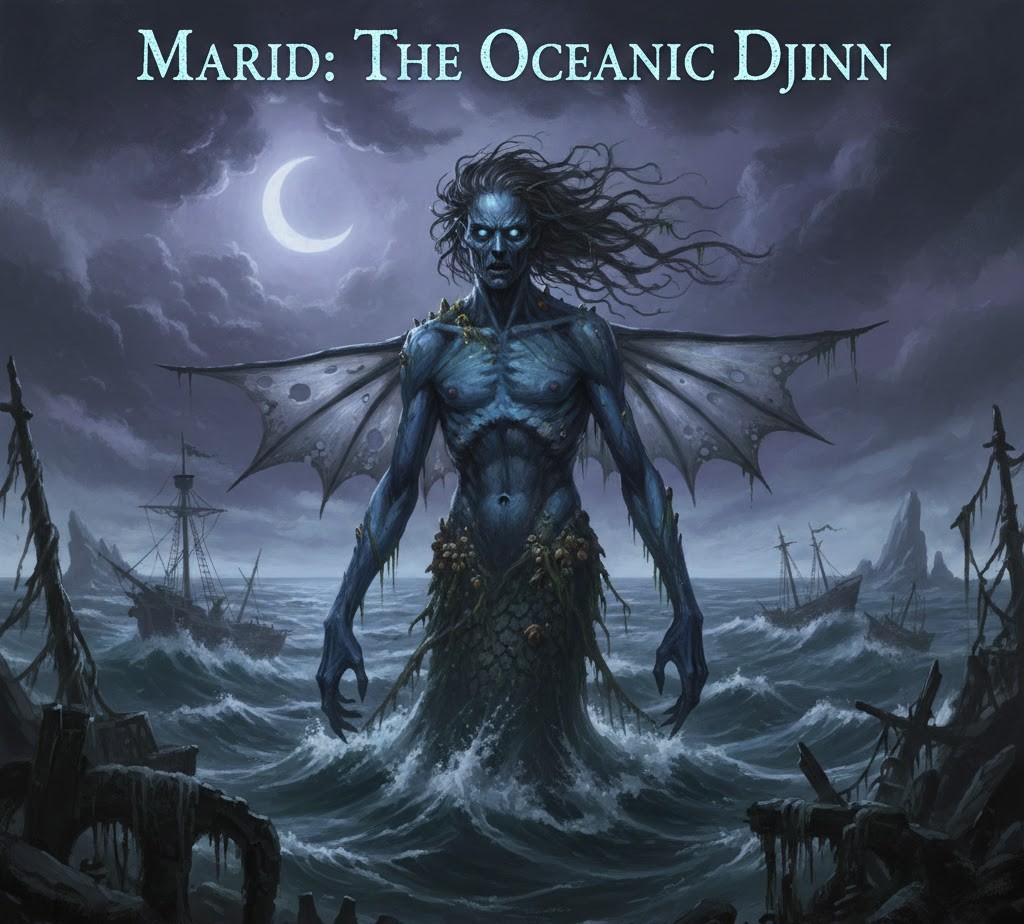

Marid – The Oceanic Djinn

The Marid are frequently portrayed as the most powerful and intellectually complex of the djinn. Often associated with water, oceans and ancient places, Marids are known for their pride, independence and structured hierarchies.

Marids may interact with humans through challenges, bargains or test of will. Unlike the Ghul, they exhibit long-term intention and identity, rather than instinct-driven behaviour. A Marid encounter often leaves the witness with a sense of being evaluated, not hunted.

This makes Marids fundamentally incompatible with Ghul behaviour, despite both being classified as djinn.

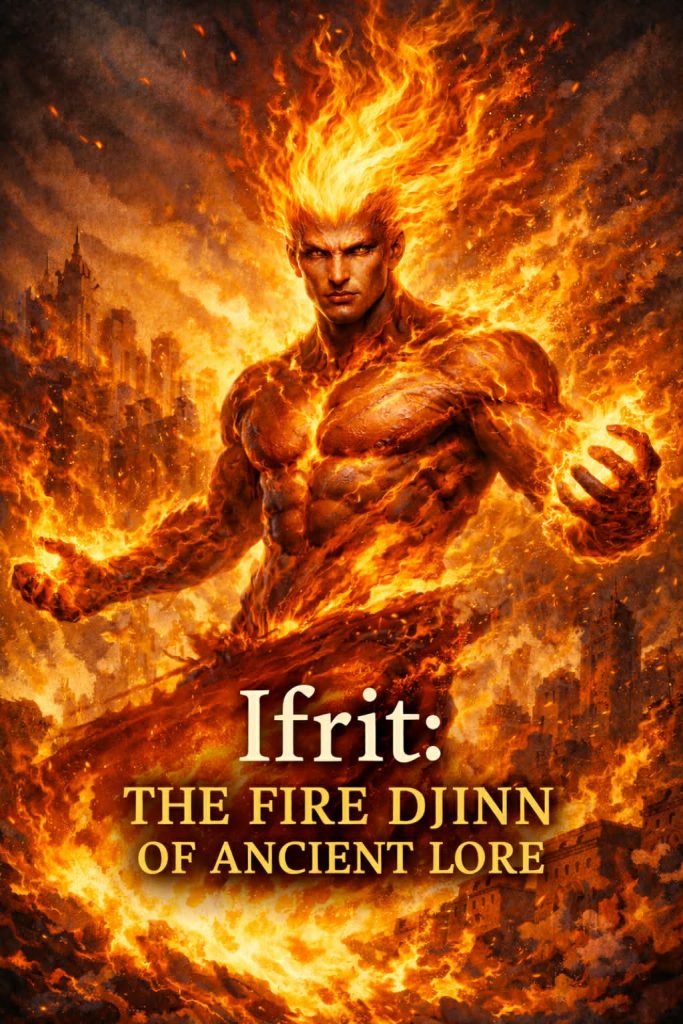

Ifrit – The Fire Djinn

Ifrits are often described as powerful, volatile djinn associated with fire, destruction and intense emotion. They are known for strength, dominance and confrontation, rather than stealth or deception.

Unlike the Ghul, an Ifrit does not rely on mimicry or subtlety. Encounters attributed to Ifrits often involve overwhelming force, violent manifestations or dramatic environmental effects. While Ifrits can be hostile, their aggression is usually reactive or confrontational, not predatory.

This difference is critical. Ghuls hunt. Ifrits clash.

Jann – The Desert Djinn

The Jann are often considered the most ancient and elemental of the djinn, associated with deserts, winds and remote landscapes. Unlike Ghuls, Jann are not inherently hostile and are frequently described as territorial rather than predatory.

Jann may avoid humans entirely unless disturbed, and when encounters do occur, they are more likely to involve environmental disturbances, disorientation or warnings rather than direct physical harm. Where the Ghul stalks and consumes, the Jann observes and defends territory.

This distinction makes the Jann a useful comparison point when investigating desert-based phenomena, as not all desert encounters indicate Ghul activity.

Shayatin – The Demonic Djinn

The Shayatin are often described as djinn that actively work to corrupt, influence or destabilise humans. Their methods are subtle and long-term, focusing on temptation, obsession and behavioural erosion.

Unlike the Ghul, Shayatin do not require physical proximity or isolation. Their influence can unfold over extended periods and does not involve corporeal feeding. Where the Ghul consumes bodies, Shayatin consume attention, emotion and intent.

This makes Shayatin a psychological and spiritual threat rather than a physical one.

Why These Distinctions Matter

From a Paranormal Down Under standpoint, collapsing all djinn into a single category obscures meaningful behavioural differences. The Ghul is not simply an “evil djinn”. It represents a specific predatory role within the non-human ecosystem.

Correctly identifying these distinctions allows investigators to assess risk accurately, interpret encounters responsibly and avoid projecting inappropriate frameworks onto phenomena that do not fit them.

Global Parallels: Predatory Non-Human Entities Aligned With the Ghul

When stripped of regional language and cultural framing, the Ghul fits into a much wider global pattern of predatory non-human entities that exist alongside humanity but operate outside normal physical ecosystems. These beings are not animals, cryptids or transformed humans. They are consistently described as intelligent, deceptive and parasitic, feeding on flesh, death or the energetic residue left behind by trauma and decay.

The following entities align closely with the Ghul in both behaviour and function, suggesting a shared underlying phenomenon interpreted differently across cultures.

The Gallu – Underworld Hunters of Ancient Mesopotamia

The Gallu of Mesopotamian belief were non-human entities associated with the boundary between the living world and the underworld. Unlike later moralised demons, Gallu were not tempters or judges; they were hunters. Their role was to seize, drag or consume human souls and bodies during moments of vulnerability, particularly illness, burial or isolation.

What places the Gallu firmly within the same classification as the Ghul is their operational environment. They were believed to gather near graves, execution sites and dying individuals – locations rich in death-related energy. Some accounts describe them imitating familiar forms or exploiting human recognition, a tactic mirrored in Ghul shapeshifting traditions.

The Gallu represent one of the earliest recorded attempts to identify a predatory intelligence that feeds at the threshold of death, rather than within normal biological cycles.

The European Ghoul – A Fragmented Transmission of the Same Entity Type

The European ghoul is not an indigenous creation but a direct linguistic descendant of the Arabic Ghul. As Middle Eastern texts entered Europe, the entity was reinterpreted through a Christian and folkloric lens, losing its djinn classification and becoming a corpse-eating grave dweller.

Despite this loss of context, the core behaviour of the entity remained unchanged. European ghouls do not command, tempt or corrupt in the theological sense. They feed. They lurk among the dead. They avoid detection. These traits align far more closely with the original Ghul than with Western demonology.

This suggests that even when belief systems attempt to redefine an entity, observed behaviour resists reinterpretation. The ghoul remains a predator, regardless of the framework imposed upon it.

Baba Yaga – A Forest-Based Predatory Intelligence

While often portrayed as a witch, Baba Yaga exhibits characteristics that extend well beyond human occult practice. She inhabits liminal forest spaces, preys upon the lost and isolated, and is consistently associated with the consumption of human flesh.

Baba Yagas deception is central to her threat. She tests, misleads and manipulates those who encounter her, drawing them deeper into her domain. Her form is inconsistent, sometimes appearing humanoid, sometimes monstrous, reinforcing the idea that her appearance is a chosen mask rather than a fixed biology.

When viewed through a paranormal lens rather than a folkloric one, Baba Yaga aligns closely with the Ghul as a regional manifestation of a predatory non-human intelligence adapted to woodland environments rather than deserts.

Rakshasas – Shape-Shifting Flesh Eaters of South Asia

In early Hindu and Buddhist traditions, Rakshasas are described as non-human entities capable of assuming human form in order to infiltrate communities. Their defining traits include deception, consumption of human flesh and a predatory relationship with fear and chaos.

Rakshasas are frequently linked to cremation grounds, battlefields and wilderness areas – spaces saturated with death and emotional residue. Their shapeshifting is not symbolic but functional, allowing them to operate undetected until they choose to feed.

This behavioural pattern mirrors that of the Ghul almost precisely.

The Aswang – Infiltrators of Death and the Grave

The Aswang of Filipino tradition encompasses several non-human entity types, many of which display strong alignment with Ghul behaviour. These entities are often described as integrating into human communities, maintaining a convincing human facade by day and feeding by night.

Certain Aswang variants are explicitly linked to graveyards and the dead, feeding on corpses or recently deceased individuals. As with the Ghul, witnesses often report subtle physical inconsistencies that betray the entities true nature, suggesting limitations in their ability to fully replicate human form.

The Aswang demonstrates that predatory non-human entities are not restricted to wilderness or isolation, but can adapt to human proximity when concealment is viable.

A Shared Behavioural Signature

Across all of these entities, a consistent behavioural signature emerges. They are not spirits of the dead. They are not animals. They are not humans transformed by curse or disease. They are non-human intelligences that exist parallel to humanity, feeding where death, fear and isolation intersect.

The Ghul in Modern Paranormal Context

Although Ghuls are often dismissed today as folklore, reports of entity encounters in deserts, cemeteries and abandoned locations continue to share striking similarities with historic descriptions. Witnesses report shape-shifting figures, unnatural movement, mimicry of human voices and overwhelming feelings of dread or disorientation.

In modern paranormal investigation, these encounters are often misclassified as shadow entities, crawlers or demonic manifestations. However, when viewed through a broader cross-cultural lens, many of these experiences align closely with traditional Ghul behaviour.

This reinforces Paranormal Down Unders belief that ancient classifications still matter. Names change, cultures evolve, but the entities themselves remain consistent.

Why the Ghul Still Matters

The Ghul represents more than a story designed to scare travellers. It reflects humanities long-standing awareness that some non-human intelligences are not passive observers, but active predators. It reminds us that not all encounters are messages, lessons or psychological projections.

Some entities feed. Some deceive. Some wait.

Understanding the Ghul helps contextualise modern reports and prevents investigators from forcing every encounter into familiar Western frameworks. In doing so, it allows us to approach the paranormal with respect, caution and historical awareness – values that remain central to Paranormal Down Unders investigative philosophy.

Final Thoughts

The Ghul stands apart not because it is more frightening than other djinn, but because it is more consistent. Across centuries of accounts, cultural boundaries and shifting belief systems, its behaviour remains largely unchanged. It hunts in isolation. It feeds where death is present. It deceived rather than confronts. These are not traits of a symbolic monster or a misunderstood spirit – they are the traits of a defined non-human intelligence operating with purpose.

Within Paranormal Down Unders approach to the paranormal, the Ghul is best understood as part of a broader ecosystem of entities that exist alongside humanity, not as relics of superstition but as recurring phenomena documented by multiple cultures. Dismissing these accounts as folklore overlooks the remarkable consistency in how these entities are described, where they appear and how they interact with the vulnerable.

Understanding the Ghul is not about fear or fascination. It is about discernment. Not all djinn are alike, and not all encounters carry the same intent. By recognising the differences between predatory entities like the Ghul and other non-human intelligences, investigators and experiencers alike are better equipped to interpret encounters accurately and respond with caution rather than assumption.

The Ghul reminds us that the paranormal is not a single narrative. It is layered, ancient and often uncomfortable. Some entities observe. Some interact. And some, quietly and patiently, wait where the living and the dead intersect.

That understanding – grounded in history, pattern recognition and lived experience – remains central to how Paranormal Down Under approaches the unseen.